Michele Abercrombie: we live(d) in our heads

My project originated from exploring my own upbringing in a seemingly normal middle class Boston household: a façade of a life of financial, emotional and physical abuse. From an early age my siblings and I were neglected, controlled and mistreated by our father. My mother wasn’t allowed to leave the house. My documentation of my upbringing with my mother’s Canon AE1 was a form of creative resistance although I didn’t know it at the time, as I was simply making images of my siblings. “we live(d) in our heads” began when I was 15 in 2008 and continues to this day.

An excerpt from my project statement, written for the “we live(d) in our heads” book I’m developing:

I’m three playing with my doll. He is yelling and it scares her—she never stops crying. My doll’s name is Leah. Leah is one.

I’m four. I’m in the bathroom talking to the creatures who live in the walls. He shouts who are you talking to. I tell him the rabbits. He tells me to hurry up and get the fuck out.

I’m six. My kindergarten friend exclaims, ‘I can’t wait for the weekend so I can stay home!’ I look at him quizzically. Home makes me uneasy. I much prefer school days.

I’m eight and I go to the playground with him and Leah. Mommy isn’t allowed to come. She doesn’t leave the house.

I’m 12 and my friend asks to come over to my house. I tell her my house is weird. I can come over to her house instead. He asks me where I’m going. Am I going over to my whore friend’s house? He tells me to sit the fuck down.

I’m 13. We don’t have internet or TV at home. We listen to the Christian radio station. I read. I spend seven to eight hours of the day reading. I average a book a day.

I’m 14 and he pushes me to the ground onto Caleb’s throw-up. He tells me to fucking clean it up.

I’m 15 and I need to use the internet to do my homework. I walk to the library. He screams at me when I return home later that evening. You fucking whore.

I’m 17 and Leah hasn’t talked in a while. It’s been almost a year. She looks like she’s in a perpetual state of shock. He calls her the Ice Queen. She looks at him, terrified. At school my art teacher asks if she’s okay. I tell her she’s just weird.

I’m 18 and he pushes me down the stairs, jumps down after me and kicks me as I lay on the floor. He had been hurting Daniel. I got in the way.

I’m 22. It’s March, 2015. I receive an email from mom. She tells me things are bad. She tells me she made a friend who will help. She tells me she’s going to leave him by May.

May 1, 2015—we call it Freedom Day.

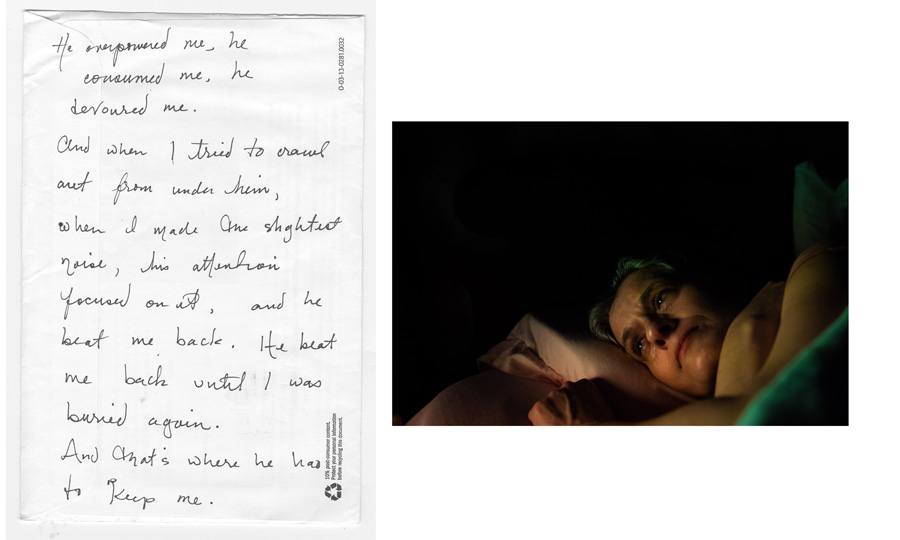

Leah sleeps on the floor of her room after discarding her bed a few days earlier. She explains that she is trying to learn self-denial in an attempt to ‘fix’ herself. “Trauma has become romanticized,” she says. Fall 2020.

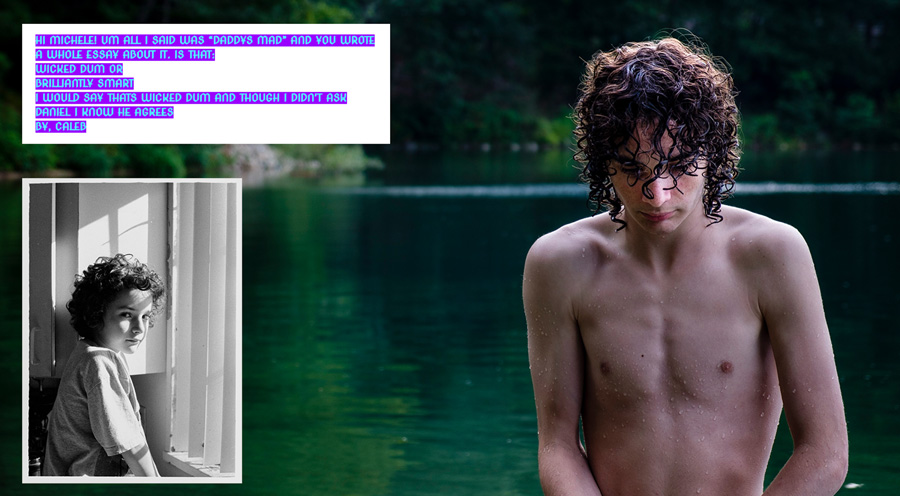

Caleb and I wrote to each other by adding to the same Google document during the spring of 2014, when I was 21 (living away from home) and he was 12. He told me what was going on and I would offer advice. Caleb’s writing in the top left is a rebuttal to advice I had recently written. The 35 film image is Caleb from 2010, when he was eight. The image at the lake is Caleb at 17, summer 2019.

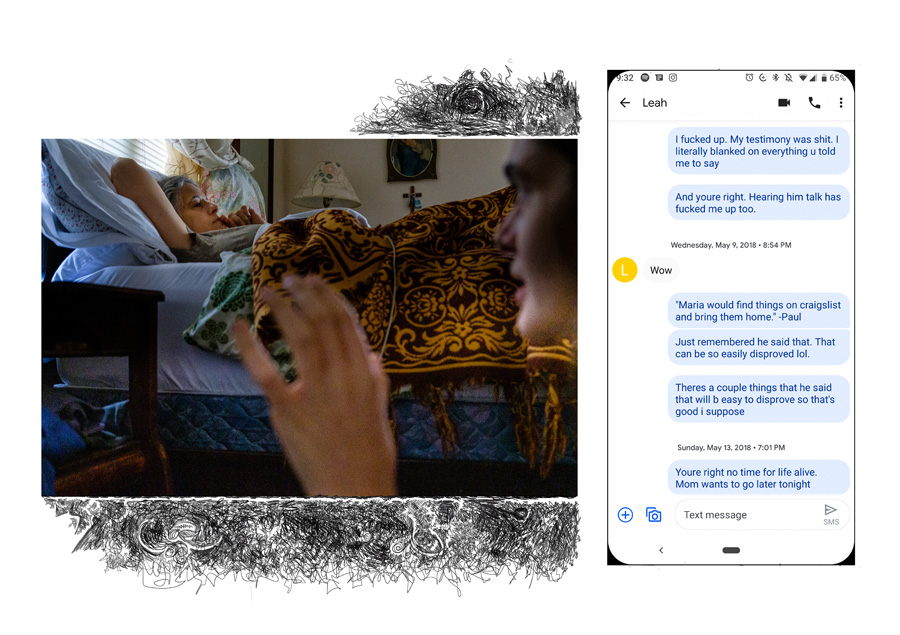

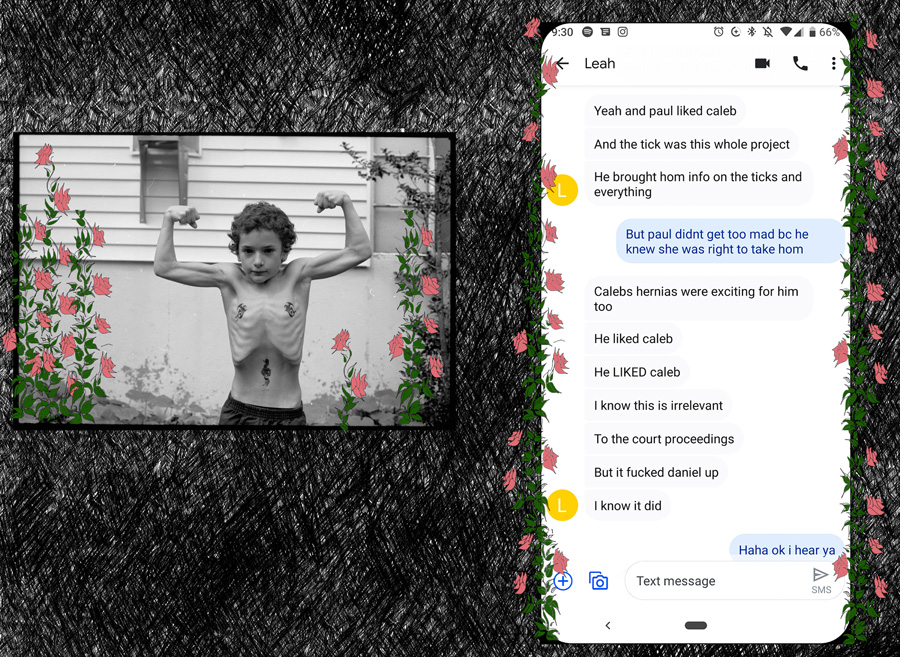

Leah sits in her mother’s room and talks about everything on her mind. This has become a daily ritual. Fall 2019. The text message is from May 2018 when I testified against my father in court for physical abuse. Leah chose not to attend.

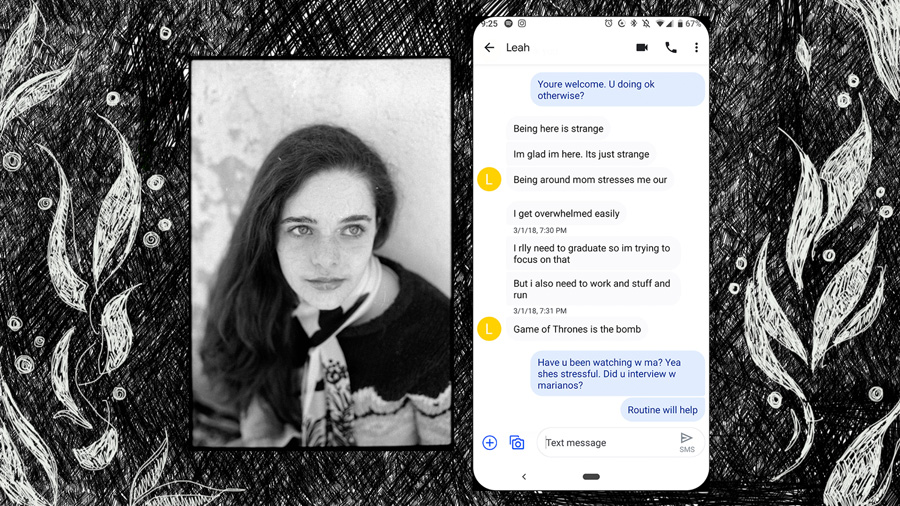

Leah, at 14. Leah left home at 18 and didn’t return until 2018, three years after our mother had left our father. She has since struggled to leave home again and has become dependent on the safe environment my mother has provided. “This is the first place I have felt safe,” Leah said of our grandmother’s home, where my mother currently resides.

Leah paces for hours at a time during the day, usually in the kitchen and otherwise will go for long walks in the neighborhood.

Maria’s writing on the back of an envelope (left). Maria watches a show on her laptop (right).

Leah Abercrombie sleeps on the floor of her room after disgarding her bed a few days earlier. She explains that she is trying to learn self-denial in an attempt to ‘fix’ herself. “Trauma has become romanticized,” she says.

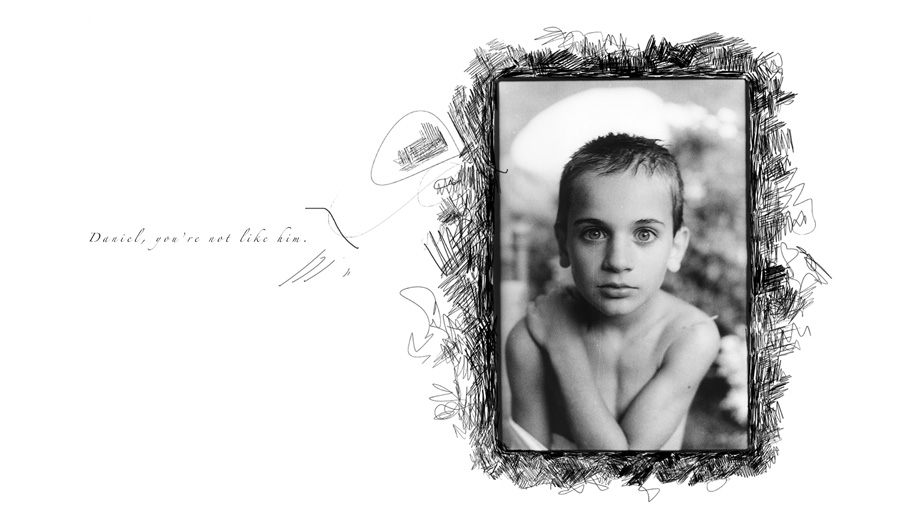

At 19, Daniel greets me when I take my camera out (left), summer 2019. As a child, Daniel always was willing to be photographed (right), summer 2010.

All families with a narcissistic parent, have one child that is the scapegoat. In our family that was Daniel. Caleb (left) was the ‘golden child’ in that he could do no wrong in our father’s eyes. Caleb was also immensely empathetic to Daniel’s plight. “The reason I hated dad is because Daniel was my best friend,” he said.

Daniel, summer 2010.

Maria Curcio relaxes in her room she shares with her daughter (the photographer). Curcio and her children all obtained restraining orders from Maria’s husband—her children’s father —in 2015. She moved into a small home with her two adult daughters and two teenage sons.

Do you remember the fairies and the flowers and the soap we would eat? Do you remember the ice queen? That’s the name he would call her but her ears were closed to him.

About Michele Abercrombie:

Michele Abercrombie, from Boston, began photographing her family with her mother’s CanonAE1 in 2008. When she left home in 2011, she rarely picked up a camera again until pursuing her graduate degree in 2018 at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. She most recently interned for News21 as a multimedia journalist for an investigation on the American juvenile justice system, with her specific focus being how families and siblings of offenders navigate the system. Her work includes film and digital photographs as well as audio, video and illustration. Themes from her current work explore family relationships, children, fantasy and trauma.