Isadora Kosofsky: Permanent and Known

Senior citizens and adults with disabilities have traditionally been left out of mainstream social justice conversations in the United States. Since I was 13, I have photographed the nuanced experiences and relationships of senior citizens and adults with disabilities in independent living and institutional contexts. When the pandemic began, I felt devastated as thousands of elders and adults with disabilities lost their lives in long-term care facilities around the country. By mid-September, 75,000 people in long-term care facilities passed away from COVID-19. Old does not equal disposable.

As I was documenting the lives of senior citizens living at home, I was drawn to the nursing home space where I first received an education on how to be with people, the basis of documentary photography, over a decade ago. State governments have restricted access inside these facilities. Yet, how do we tell the story of a war without showing where the bombs have been dropped? We are present at the frontlines of conflict yet, by August, I still had not seen intimate documentation of long-term care residents with COVID-19.

With its beige walls and fluorescent lighting, the Canyon Transitional Rehabilitation Center in Albuquerque has all the hallmarks of a nursing home. Yet, the hallways are devoid of residents. The doors of all 44 rooms are shut tight. All 70 residents have COVID-19.

After a four-month process, I received state government approval and entered Canyon to document the relationships between COVID-positive residents and certified nursing assistants. Nursing homes are a nexus of senior rights, disability rights, women’s rights and immigrant labor rights. One in four long-term care workers are immigrants. In the face of the pandemic, certified nursing assistants and caregivers are overlooked as front-line workers. Nursing homes are the forgotten institutions.

Outside congregate living settings, I shadow seniors who live independently, as they navigate loneliness, social isolation and new ways of being intimate without physical proximity. I attempt to reveal loneliness, social isolation and living alone as distinct and sometimes separate subject matters. Loneliness, a subjective feeling, can exist without social isolation. Social isolation, a sociological construct, can be measured objectively and can exist without loneliness. I document how senior citizens and adults with disabilities cope with the pandemic and the closure of day programs through new interests, previous passions and the use of technology.

Through this multi-series documentation that looks at age, disability and COVID-19, aloneness, grief and survival are revealed as personal and subjective human experiences. I will continue to document how senior citizens and adults with disabilities are finding means to subsist through this unprecedented period. I will also expand the project to include documentation of hospice care for those with COVID-19 in an attempt to study loss and bereavement. The work aims to make permanent and known the lives of those rendered anonymous and dispensable. I endeavor to elevate senior rights and disability rights as forefront social justice issues during and after the pandemic through traditional publication, exhibition in intergenerational spaces, and public presentation.

Leslie Riggins, 66, who has COVID-19, in her bed at night at the Canyon Transitional Rehabilitation Center in Albuquerque. Leslie, a former public school teacher, contracted the virus at another nursing home where she resides in Albuquerque. “To be able to survive you have to have simple pleasures like green grass and little birds, otherwise you go nuts,” said Leslie. In the midst of fear and loss, residents and caregivers find relief in quiet moments of connection behind the closed doors. “You know, grandma is really worth something,” said Leslie.

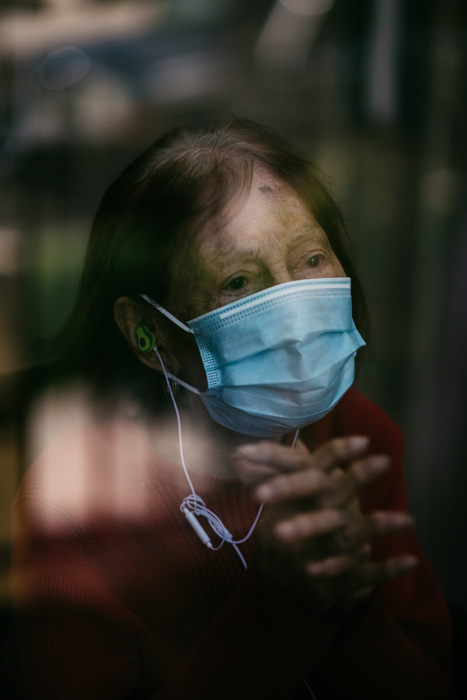

Fabiola Toralba, 95, looks at her daughters, Cecelia, Gemma and Marifa and grandson, Anthony, as they stand on the other side of a glass door at the Alexandria Care Center in Los Angeles on Mother’s Day. Fabiola listens to Gemma read The Lord’s Prayer through Facebook messenger.

A light switch in Shane’s, 90, apartment in Santa Monica.

Maika Alvarez holds an iPad, as Jose Montoya, 94, interacts with his daughter, Lillie Ortiz, via Facetime. Mr. Montoya is a World War II veteran. “It’s difficult for those of us family members. We are crushed by the helpless position we are in. We cannot hold our loved one’s hand and comfort them by our presence. The only thing that reaches them is our prayers because they are quarantined behind locked doors,” said Ortiz. “It isn’t until COVID hits a nursing home that you see the snowballing effect of its unpredictability and of its devastation.” Jose Montoya passed away on September 13.

Shane, 90, sits on a bench by the beach in Santa Monica, California after a walk. Shane has lived at in front of an affordable housing apartment complex for seniors and adults with disabilities in Santa Monica for eleven years. Thirty years ago, he emigrated from Iran where he was a banker to the United States. In the US, he became a business owner, operating a yogurt shop and a print store. Now that he is retired, he spends most of his time in his apartment, listening to Farsi radio that he streams off his iPad. Due to macular degeneration, he is unable to read or watch television. Currently, visitors, other than healthcare providers, are banned from the community where he resides. When Shane’s brother visits him, they talk from a distance on the sidewalk. “I don’t have it, yet,” he says when asked about the impact of the virus on his life.

Alice, 84, who has COVID-19, holds a photograph of her granddaughter at the Canyon Transitional Rehabilitation Center in Albuquerque. “I miss my family a whole lot.” Canyon, an entirely COVID+ setting, is a nursing home that houses residents with COVID-19 from other long-term care facilities in New Mexico. “I’m missing my grandchildren’s birthdays,” she said. Alice has 9 grandchildren. She keeps the heart-shaped photograph of her 18-year-old granddaughter in her Bible. “Today, I am lonely, but I’m strong. I know what I’ve been through,” said Alice.

Shane, 90, looks out the window of his apartment at a community for seniors and adults with disabilities in Santa Monica, California. Shane has lived alone at this building for eleven years. He emigrated from Iran to the United States thirty years ago. He spends most of his time in his apartment, listening to Farsi radio that he streams off his iPad. Due to macular degeneration, he is unable to read or watch television. When he looks out his window, he only sees the outline of trees, car and people. Currently, visitors, other than healthcare providers, are banned from the community. When Shane’s brother visits him, they talk at a social distance from the sidewalk. “I don’t have it, yet,” he says when asked about the impact of the virus on his life.

Edgar, 93, sits on his lawn with his granddaughter during a socially distant visit in Los Angeles, California. Before the pandemic, Edgar visited the neighborhood senior center for lunch and activities. The senior center has been closed since March. Edgar considers himself a more fortunate senior citizen residing alone, as one of his kids visits him per day. “Every time I think of my kids, I think how lucky I am,” he says of his three children. For now, his son who is a doctor does not visit. Edgar has lived alone for the past 9 years since the death of his wife, Frida. Edgar is a Holocaust survivor who was born in Berlin. He emigrated to the St Louis, Missouri in 1947 after waiting in the United Kingdom to receive permission to emigrate. Once arriving in the United Kingdom via The Netherlands, he was detained with his family on the Isle of Man until British authorities could confirm that they were Jewish. His wife, Frida, was a Polish survivor of Aushwitz and Mauthausen. Edgar’s earliest memories are of Kristallnacht when he witnessed the desecration of Jewish stores and properties. Both Edgar and Frida have lectured at high schools about their experiences of the Holocaust. Educated in engineering, Edgar spent most of his adult life as a toy inventor for Mattel. He is the creator of the famed toy, Creepy Crawlers. Edgar continues to invent today in his living room and also writes children’s books. During the pandemic, Edgar reads, gardens and cleans his home. “Busy keeps me happy,” Edgar says. “Due to the coronavirus, all these things become important because you can’t do anything else.”

Juanita Lujan, 94, who has COVID-19, in her room at Canyon Transitional Rehabilitation Center in Albuquerque. Ms. Lujan was moved from the retirement community where she resides in Las Cruces after she contracted COVID-19. Lujan spent most of her career working in the kitchen and cafeterias in the Las Cruces Public School system. Ms. Lujan has 5 children, 12 grandchildren and 15 great grandchildren. “They didn’t explain,” she said of her move. “It’s ok. I’m not complaining…I just want strength to crochet and draw.”

About Isadora Kosofsky:

Isadora Kosofsky is a documentary photographer based in Los Angeles and Albuquerque. She began photographing at the age of 14, documenting individuals in hospice care. She takes an immersive approach to visual storytelling, spending months and years embedded in the lives of the people she shadows. She works on a range of subject matters through the lens of one individual or group of people, looking at mental health, incarceration, substance use, disability rights, gender violences, childhood trauma and senior citizen rights, documenting from an interpersonal, humanistic stance.

Kosofsky is a National Geographic photographer. She also contributes to the New York Times, TIME, The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, the Washington Post, Stern, Le Monde, M le Magazine du Monde, GEO Germany, Paris Match, The London Sunday Times, the Guardian, Slate, Internazionale and many others. She is the recipient of the 2012 Inge Morath Award from the Magnum Foundation for her multi-series work on the aged. She was nominated for a 2016 Lead Award (German Pulitzer) for her long-term documentary about a senior citizen love triangle. She was a participant in the 2014 Joop Swart Masterclass of World Press Photo. Her work has received distinctions from Flash Forward Magenta Foundation, Ian Parry Foundation, Social Documentary Network, International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Women in Photography International, Prix de la Photographie Paris, The New York Photo Festival and others. Her work is in the permanent collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and can be found in Family Photography Now (Thames and Hudson, 2016), a photographic anthology, and in Public Private Portraiture from Mossless. She had an exhibition of her work on youth facing incarceration and their families at the 2017 Visa Pour L’Image International Festival of Photojournalism in Perpignan, France. She is the recipient of a 2017 Getty Images Instagram Grant for elevating the stories of marginalized communities.

In addition, she is a teacher and has lectured at CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, Ohio University School of Visual Communication, Loyola Marymount University, Harold Washington College, the National Conference on Crime and Delinquency, and has instructed high school students on topics related to the language of empathy, working intimately with subjects, and trauma studies. She is a recipient of a 2018 Grant from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting. In 2019, the Royal Photographic Society named her one of a hundred “heroines” in photography worldwide. Kosofsky is a TED Fellow, part of a network of 450 global change makers, and gave a talk at TED 2018 in Vancouver. She is a 2020 Gwen Ifill Mentor through the International Women’s Media Foundation. Kosofsky’s first monograph, Senior Love Triangle, was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2020 and is now available on Amazon and in bookstores.